Wer war/ist Joe Barry ? - CDs, Vinyl LPs, DVD und mehr

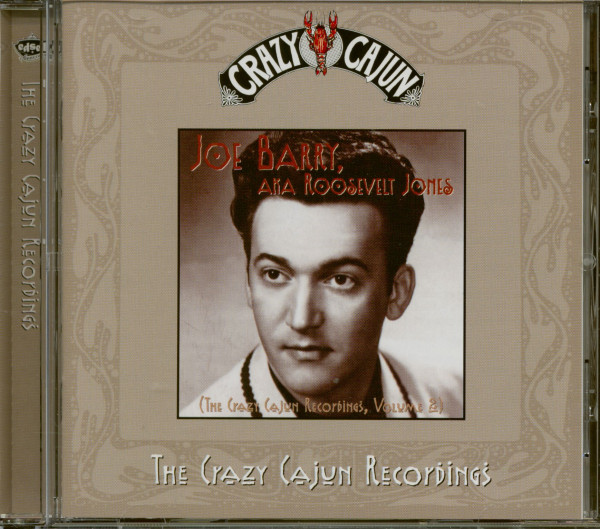

Joe Barry

When reading of the Cajun/Swamp Pop musician Joe Barry, time and time again one comes across the word "legend". He has indeed cut a wide swath, both musically and as a sort of Cajun Kali, a bayou-born god of destruction. Survivor of thousands of binges and a pioneer of the fine art of hotel room disassembly, it should not be forgotten that Barry was one of Acadiana's most talented musicians to emerge in the 1950's and 60's.

Born dirt-poor on 13 July, 1939 in the isolated, swampy area below New Orleans in Cut Off, Louisiana, Joseph Barrios was the son of a river-pilot father and a sugarcane-cutting mother. His was a most stereotypically Cajun childhood. Contrary to the Hollywood-fuelled myth, most Cajuns are not swamp-dwellers. The vast majority of them live on bayou-streaked prairies, where they cultivate rice, sugar, and sweet potatoes. But Barry was the exception that proved the myth: his father augmented the family cookpot with poached alligator and muskrat-meat, amply furnished by the swamp's bounty. Like many Cajun families, music was as vital to the Barrios clan as shopping is to Anglo-America. His father played Jew's harp and harmonica, and as he related to Shane Bernard in "Swamp Pop: Cajun & Creole Rhythm & Blues", pickers were thick on the ground in the rest of his family as well. "Vin Bruce is my cousin... he recorded for Columbia way before anybody thought of it... Lee Martin is my cousin. He played music all his life... Before that, my mama's side alone... they had about six or seven in the family who played musical instruments."

Born dirt-poor on 13 July, 1939 in the isolated, swampy area below New Orleans in Cut Off, Louisiana, Joseph Barrios was the son of a river-pilot father and a sugarcane-cutting mother. His was a most stereotypically Cajun childhood. Contrary to the Hollywood-fuelled myth, most Cajuns are not swamp-dwellers. The vast majority of them live on bayou-streaked prairies, where they cultivate rice, sugar, and sweet potatoes. But Barry was the exception that proved the myth: his father augmented the family cookpot with poached alligator and muskrat-meat, amply furnished by the swamp's bounty. Like many Cajun families, music was as vital to the Barrios clan as shopping is to Anglo-America. His father played Jew's harp and harmonica, and as he related to Shane Bernard in "Swamp Pop: Cajun & Creole Rhythm & Blues", pickers were thick on the ground in the rest of his family as well. "Vin Bruce is my cousin... he recorded for Columbia way before anybody thought of it... Lee Martin is my cousin. He played music all his life... Before that, my mama's side alone... they had about six or seven in the family who played musical instruments."

It was Vin Bruce who thrilled young Barry most, and he was often sent to chaperone his older sister at fais-do-dos at which Bruce played. If as a chaperone he was a dismal failure ("I couldn't give a damn what she was doing. I wanted to hear the band," he told Bernard) at least he was picking up some chops. Around the age of eight, the precocious Barry had progressed through a series of increasingly sophisticated guitars to the mastery of a real-life grown-up model. He began to sit in at some of the rowdy all-night fais do-dos at this tender age, his father's fearsome reputation as a brawler protecting the child from anything untoward.

Meanwhile, the inquisitive Barry was soaking up the sounds of Ernest Tubb, Hank Williams, and Roy Acuff emanating from Nashville on the Grand Ole Opry, and stealing away from the staid Latin Masses of the Cajuns to attend the wild, joyous, sanctified African American country services. To a greater extent than most of his fellow Swamp Poppers, jazz was also a vital component of his musical apprenticeship, with Barry eventually studying the form in New Orleans under no less a pair of authorities than trumpeter Al Hirt and clarinettist Pete Fountain. Also from New Orleans was the hugely popular R&B epitomized by Smiley Lewis and Fats Domino, perhaps the most important ingredient in the Swamp Pop gumbo of a sound that Barry helped to create. By the early fifties, Barry was playing traditional Cajun, country, and jazz professionally, and his eclecticism was beginning to chafe on some of his more hidebound bandmates. To their peril as it turned out. "I went into a fever, called the south Louisiana fever," he told Bernard, "which had a little beat in the country songs which the country entertainers back then did not go for.

So they said, 'Well Joe, you can sit in, but are you gonna play that funny stuff?' And I said 'Yeah, I'm gonna play that funny stuff.' And they'd laugh at me, poke fun. So I'd take an old Gene Autry tune like 'I'm A Fool to Care' and I'd hit a little different note on it, you know, with the beat. And the kids started liking it, ...and some of the grown-ups starting liking it. So finally the guys that were the big stars in the local bayou country wouldn't let me sit in with their bands because I kept singing this funny stuff- the club owners were asking me to replace them." In the late 50's Barry made New Orleans a second home, sitting in with such legends as Smiley Lewis, Tommy Ridgely, and "Sugar Boy" Crawford. By 1958, he considered his apprenticeship complete and founded his first band, a nine piece Swamp Pop outfit called the Dukes of Rhythm. The band recorded little of note, and Barry left to form the Delphis. In 1960 the Delphis scored a small regional hit with "Greatest Moment of My Life" / "Heartbroken Love" on the Jin label. Though the record did not sell tremendously well, legendary Swamp Pop producer Floyd Soileau was taken enough with Barry's talents to schedule him a session at Cosimo Matassa's fabled New Orleans studio. Backed by the Vikings, a hastily-arranged outfit comprised of high school students, Barry recorded the Ray Charles-influenced "I Got A Feeling" and "I'm A Fool to Care" at Matassa's studio. The band was bitterly divided over which was the a-side of the single, with Barry favoring "I Got A Feeling".  They decided to let more objective observers decide the matter. "Let's take it to someplace that can really test it out", Barry recalls saying. "We went to this whorehouse, put it on the jukebox. They all liked "I'm A Fool To Care". I was pissed off, boy". As they were to do with Tommy McLain's "Sweet Dreams" a few years later, the Cajun ladies of leisure made an astute A&R decision. Why they didn't pool their resources and open their own label is a mystery. Soileau was just as delighted with "I'm A Fool to Care", calling in Huey Meaux to promote the record, which was an instant regional smash. Smash (a Mercury imprint), fittingly, was the label that leased the tune from Meaux and Soileau, and with their distribution and promotion the song peaked at # 24 on the Billboard chart in the summer of '61.

They decided to let more objective observers decide the matter. "Let's take it to someplace that can really test it out", Barry recalls saying. "We went to this whorehouse, put it on the jukebox. They all liked "I'm A Fool To Care". I was pissed off, boy". As they were to do with Tommy McLain's "Sweet Dreams" a few years later, the Cajun ladies of leisure made an astute A&R decision. Why they didn't pool their resources and open their own label is a mystery. Soileau was just as delighted with "I'm A Fool to Care", calling in Huey Meaux to promote the record, which was an instant regional smash. Smash (a Mercury imprint), fittingly, was the label that leased the tune from Meaux and Soileau, and with their distribution and promotion the song peaked at # 24 on the Billboard chart in the summer of '61.

Barry had a brief turn in the high cotton of the day, appearing on Dick Clark's American Bandstand television program (an appearance that had the unforeseen consequence of alienating Barry's nascent black audience, who were expecting a somewhat darker-hued Barry to step in front of the cameras). A French-language version of the song, le suis bet pour t'aimer" was released hard on the heels of its Anglo counterpart, attracting new fans in both Quebec and France. The success of "I'm A Fool to Care" also won Barry an enthusiastic following from another unexpected quarter. "I had made good contacts with the Jewish syndicate, Greek syndicate, and Italian syndicate once you get in with them, the bookings run." These gigs took Barry far from the beer-soaked dance halls of south Louisiana. Swanky East Coast night-clubs and Vegas casino venues instead became his haunts in this "Goodfella" interlude of which Barry has only fond memories. "They were great with me, man", he said, and when asked if they had taken over his management, he told Bernard, "No. You know, they tried one time to get in my contract — well, if I'd have been smart, I'd have let them, really, 'cause I don't think they'd have robbed me as bad as I did get robbed." The rest of the early 60's passed without Barry successfully following up "I'm A Fool to Care", although he did post a minor chart record with "Teardrops In My Heart". He continued to record for Jin/Smash, and also recorded R&B for other labels (including some of Huey Meaux's) under the "black-sounding" pseudonym Roosevelt Jones, which had the dual function of concealment from existing contracts and targeting a black audience. By 1965, he left Jin to record 12 singles for the Princess label.

This period also was fruitful on stage. He was a part of a little-known super-group, a never-recorded aggregation of legendary musicians. The venue was Papa Joe's strip club in the New Orleans' French Quarter, and the band included Barry, Houston blues legend Joey Long, Skip Easterling, and a duo of freshly paroled musicians of some note: namely Freddy Fender and the pre-Dr. John Mac Rebennack. As Barry recalled, "We had the hottest thing in the Quarter going... (after the strippers show) we'd start a jam session from three in the morning on... Sometimes we'd go until noon... But in those days we were so pilled up we could have went 48 hours. So the shows got bigger and bigger and drawing more and more people... and you got people fighting, I mean fist-fighting to get in there... people just coming in at midnight and booing the strippers, that wanted the band. That's weird for New Orleans."

By 1967, Barry had enough. His Keith Moon-like escapades, which predated Moon's own, were indeed monumental. Small fires followed in his in his dreadful wake. A Barry-wracked Holiday Inn room once claimed "Most Destroyed Room" at that chain's national convention. He pioneered a method of escaping a motel room that was locked from without, as he was often locked in his room by those who wished to protect him from his vices. He quickly discovered that the Achilles heel of any motel room was its telephone jack, and judicious tugging at the telephone wire would create a chink that could then be relatively easily enlarged into a man-sized hole. His appetites for liquor and pills were as gargantuan as his penchant for devastation, and one can continue along in such a manner for only so long. Tired of such shenanigans, Barry retired from music to roughneck on the Louisiana oil rigs, only to return to the studio less than three years later. In the early '70's, Barry renounced once and for all his wicked past, and embraced religion. He has recorded fitfully since the late '60's, with some of even those few records never seeing the light of day. He has worked as used-car salesman back in his native Cut Off, and preached the Gospel in Africa and the Caribbean. Bad luck and trouble dogged him

in the mid-80's, as his faith wavered in the wake of the Swaggart and Bakker sex scandals, and his health collapsed. He was penniless and ill, living in a house with no water or electricity, when a kicked-over lantern resulted in the destruction of even that humble abode. He could not possibly have bottomed out more dramatically, yet his faith, though shaken, sustained him. His old friends began to rally round, with Swamp Poppers like Rod Bernard, Clint West, and T.K. Hulin performing a series of benefits for him in the early 90's. As of 1996, he regained enough of his health to perform in support of his two unreleased records on his own New Dawn label.

While certainly one of Louisiana music's great characters, Barry's outstanding musicianship should not be overshadowed by his legendary capers. Those that didn't know him in his wilder days can only listen to and read the stories of that earlier Joe Barry, and with the passage of time those legends will fade. Lucky for us that he has also made his mark on the world with his music, and here's hoping this tough-as-nails Cajun can get off the mat one more time.

John Nova Lomax, April 1999

Copyright © Bear Family Records® Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Nachdruck, auch auszugsweise, oder jede andere Art der Wiedergabe, einschließlich Aufnahme in elektronische Datenbanken und Vervielfältigung auf Datenträgern, in deutscher oder jeder anderen Sprache nur mit schriftlicher Genehmigung der Bear Family Records® GmbH.

Sofort versandfertig, Lieferzeit** 1-3 Werktage

Artikel muss bestellt werden