With ‘R&B in DC 1940-1960,’ historian Jay Bruder reacquaints us with the sounds of a vanished Washington

The Impalas, later known as the Jewels or Four Jewels. (Courtesy of the Jewels)

By Chris Richards

Pop music critic

Today at 6:00 a.m. EDT

When we listen to a recording of an old song — say, the D.C. nightclub semi-fixture Eva Foster singing “You’ll Never Know” roughly 68 years ago — something excellent happens: the air that surrounds us shakes the same way it shook in 1953. Is there anything else like it? Old music might plunge our imaginations into the past, but more tangibly, it changes the physical reality directly outside of our heads. Listening to an old song isn’t a revisitation. It’s a material reenactment. Then happens now.

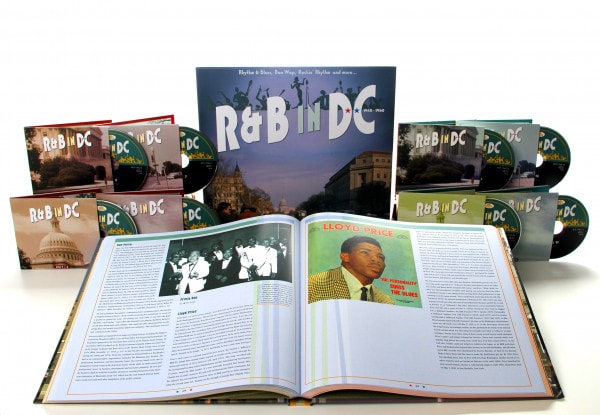

A sweeping and scrupulous new boxed-set, “R&B in DC 1940-60,” does this little trick 472 times. Compiled and produced by music historian, DJ and record collector Jay Bruder, and released by the German label Bear Family Records, the set features more than 20 hours of blues, doo-wop, jazz, classic R&B, proto-rock-and-roll and other hybrid styles of Black dance music made in Washington decades ago, conjuring the sound of a largely vanished city in startling detail.

The “R&B in DC 1940-1960” box set features more than 20 hours of tunes. (Bear Family Records)

How startling? “Beyond painstaking” probably sells Bruder short. The 352-page coffee table tome anchoring this set examines the scene on a granular level, with Bruder chasing down every scrap of lore until the trail fades into the mist of unknowability. Having scoured old newspaper clips, copyright records, studio and label paperwork, Yellow Pages advertisements and more, he maps out a teeming network of high schools, churches, nightclubs, recording studios, record labels, radio stations and television programs that made this scene pulse for two decades.

As for the music itself, it encompasses nearly 500 songs spanning 16 compact discs — and while it includes a pocketful of tunes you might remember (The Clovers’ “Love Potion No. 9,” a moderate hit immortalized decades later on oldies radio), it’s brimming with forgotten obscurities you won’t (“You’ll Never Know,” Foster’s dazzling dud with the Van Perry Quintet, among so many other shouda-beens).

Maybe “forgotten” is an insufficient word, too. In the book’s early pages, Bruder unveils his thesis while marveling at “Could I Adore You,” a tenderly haunting a cappella tune sung by the Blue Jays, a group of Francis Junior High School students who amassed their recording budget of $1.25 by cashing in glass bottles they had collected in Rock Creek Park. Once they had enough coin in hand, they headed to Circle Recording Studio on Pennsylvania Avenue NW to record “Could I Adore You” onto a black lacquer disc. The record was one-of-one, cut in a single take.

The Blue Jays “were not so much forgotten as unremembered,” Bruder writes. “They were unremembered in that lazy habit of historical redaction which constantly resurfaces the very most familiar names, jazz legend Duke Ellington, soul music superstar Marvin Gaye and Chuck Brown, ‘The Godfather of Go-Go,’ at the expense of the hundreds of artists and entrepreneurs who, in their own way, contributed so much to Washington’s history in music.”

Each of those contributions has its own little creation myth, and Bruder unearths as many as possible to help us better understand this extraordinary music. The reason Lloyd Price’s cascading melody on 1957’s “Just Because” feels so timeless might have something to do with the fact that he cribbed it from a Verdi opera he heard on WGMS while cruising around town. The reason that the guitar solo on the Impalas’ 1961 single “For the Love of Mike” feels so jittery and alive is probably because the guitarist is none other than Bo Diddley. (The Impalas rehearsed in his basement on Rhode Island Avenue NE.) And the reason Billy Stewart’s heart-in-throat staccato sounds so confident during his 1958 single “Billy’s Heartache” might be because the backup vocalists are the Marquees, a group featuring a young Marvin Gaye. The guitar sounds great on “Billy’s Heartache,” too. Diddley again.

<image005.jpg>

Tommy “TNT” Tribble (senior and junior). (DC Records)

<image006.jpg>

The Cap-Tans. (DC Records)

This isn’t just a trove of record-collector trivia, though. Bruder’s tenacious attention to detail can help tune your ears to this music’s ability to cram immense sensations into musical nano-spaces. Listen to the torquing five-second intro of the TNT Tribble Orchestra’s “Red Hot Boogie” and feel the universe spin. Listen for the moment Eddie Daye of the Four Bars opens his mouth on “Grief By Day, Grief By Night” and see if you can’t hear the bandleader holding the cosmos in his yawning basso.

Of course, “R&B in DC” also tells the story of a city, namely of Black life in segregated, postwar, forever-in-flux Washington. Most of the songs assembled here served as party music, dance music, nightclub music, sock hop music, jukebox music — the sound of Black Washingtonians enjoying a moment of prosperity after wartime, or at least trying to catch a glimpse of it.

“T.V. Boogie Blues,” a 1952 collaboration between two scene heavies — drummer Tommy “TNT” Tribble and trumpeter Frank Motley — suggests that the spoils of the era remained out of reach for many. “I got no down payment,” Tribble sings, bemoaning a pricey new technology over a jumpy nascent rock rhythm. “My baby’s got the T.V. blues.”

It seems that the most successful musicians in the city were still struggling, save for a few. The Clovers were among the starriest D.C.-minted acts of the era, having recorded piles of hit singles for Atlantic Records in the label’s relatively lean and early days. Their success helped the District-raised record mogul Ahmet Ertegun take a big bite of this world, but with Atlantic still on the rise in New York in the late 1940s, Ertegun hustled to keep his hometown power-people happy, dedicating certain Atlantic singles to District DJs, including “Lowe Groovin’ ” by Joe Morris and his Orchestra, a flattery-for-play token memorializing the District radio personality Jackson Lowe.

Ertegun wasn’t the only one gaming the scene from out of town. More than a handful of songs on this tracklist are wink-nudge odes to Max “Waxie Maxie” Silverman, an entrepreneur whose original Quality Music shop on Seventh Street NW eventually bloomed into the Waxie Maxie’s record store chain.

<image007.jpg>

A spread from the companion book packaged with the “R&B in DC” box set. (Bear Family Records)

Other local record label founders — the omnivorous Lillian Claiborne of DC Records, the intrepid Ben Adelman of Empire Records, and others — had tremendous musical savvy but not enough of the marketing expertise necessary to make their labels a major as Atlantic. That means the tracklist of “R&B in DC” is overflowing with beautiful dead ends.

Throughout his 1960 single “I Feel Allright,” the Warrenton, Va.-born Sammy Fitzhugh hits a series of teakettle notes that feel more vivid than life. And yes, he’s singing an imitation of the Isley Brothers’ “Shout!,” but wouldn’t we be better off hearing this song at every wedding reception for the rest of time? Bruder sums up the flop with a common refrain: “This was another fine performance from a talented Washingtonian which failed to make the national charts.”

What is it about Washington’s music that so often keeps it sealed inside the city limits? The lack of music industry infrastructure? The perpetual exodus of Marvin Gaye-sized talent? The absence of an easily marketable style or sound? Maybe this city has always been best at singing to itself. Maybe that’s its strength, not its weakness.

<image008.jpg>

Frank Motley often played with two trumpets at once. (DC Records)

As far as fingerprints go, according to Bruder, the District’s greater R&B ecosystem did have a few aesthetic tendencies across these two decades — a long-standing tradition of austere, close harmony street singing, and a by-and-large preference for jazz over the blues. And in any scene without dogma, the weirdos get weird. Check out Pat Patterson’s 1960 single “Rat-A-Ma-Cue,” a stream-of-consciousness rhythm-babble that sounds like future-blues. He has a freaky neighbor in Frank Motley’s “Space Age” from 1959, a song where Motley — who liked to play two trumpets at once — swaddled his bleats in exospheric reverb.

Obviously, reverb wasn’t an effect exclusive to District recording studios, but the city’s R&B artists may have heard its echoes differently. Motley had already used it to disorienting effect on “Frantic” from 1953. Earlston Ford’s buttercream croon turns sharp and penetrating thanks to the reverb on “He Made Us All” from 1956. On her 1958 single “I Cried the Last Time,” Delores “Baby Dee” Spriggs — a veteran singer who began her recording career as a teenager more than a decade earlier — sounds as if she’s wandering an empty city alone.

Inside Bruder’s book, archival images show a Washington cityscape that only still half-exists today. So much of the District was burned in the riots of 1968, and even more of it has since been wrecking-balled into condo hell. But there are also a few photos here of the stony, federal buildings downtown — and if you’ve ever spent the tiny hours of the night in Washington’s most permanent places, you might have something in common with the musicians who lived and worked here 70 years ago. You know how sounds bounce off those buildings in the city’s loneliest, emptiest hours. Laughter. Footsteps. Music pouring from the open window of a passing car. This city’s music echoes across space and time in more ways than one.

Read more by Chris Richards:

Charlie Watts was a gentleman in the world’s most dangerous band

Two saxophone masters delivered resonance in pandemic times — but one of them sounded a bad note on vaccines

The world is fast. Bad Brains are faster.

By Chris Richards

Chris Richards has been The Washington Post's pop music critic since 2009. Before joining The Post, he freelanced for various music publications.

Various - History R&B in DC 1940-1960 - Rhythm & Blues, Doo Wop, Rockin’ Rhythm and more… The Washington Post

Kommentar schreiben

Passende Artikel